Theme

International Dimensions

INSTITUTION

Hospital for Sick Children, Department of Paediatrics, University of Toronto

Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto

Mount SInai Hospital, University of Toronto

Global health (GH), and interest within medicine in partnering with resource-poor areas (RPAs), has dramatically increased over the last few decades including:

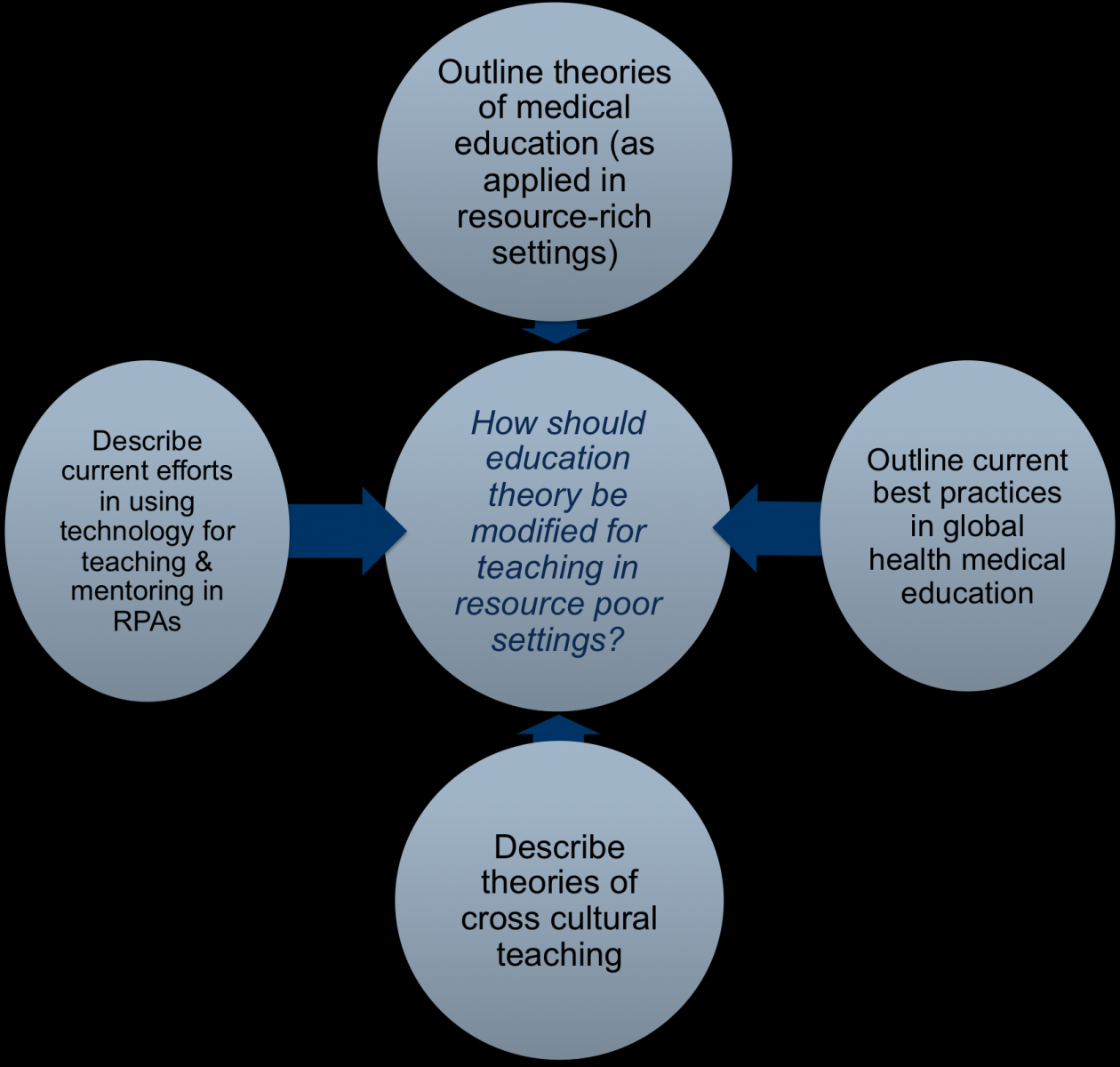

Little scholarship has been done in global health medical education (GHMEd) regarding how teaching principles should be applied in RPAs.

As practices of inter-regional education become more widespread, there is an impetus to look at theories of education to see how they can be modified for application in resource poor settings.

The purpose of this work is to amalgamate theories of learning in medical education and of cross cultural teaching with experience in resource poor areas and technology use in GH to create a novel model of education for two purposes:

1. to be applied when teaching in RPAs

2. for use as a framework to build evidence and create discussion around best practice in GHMEd.

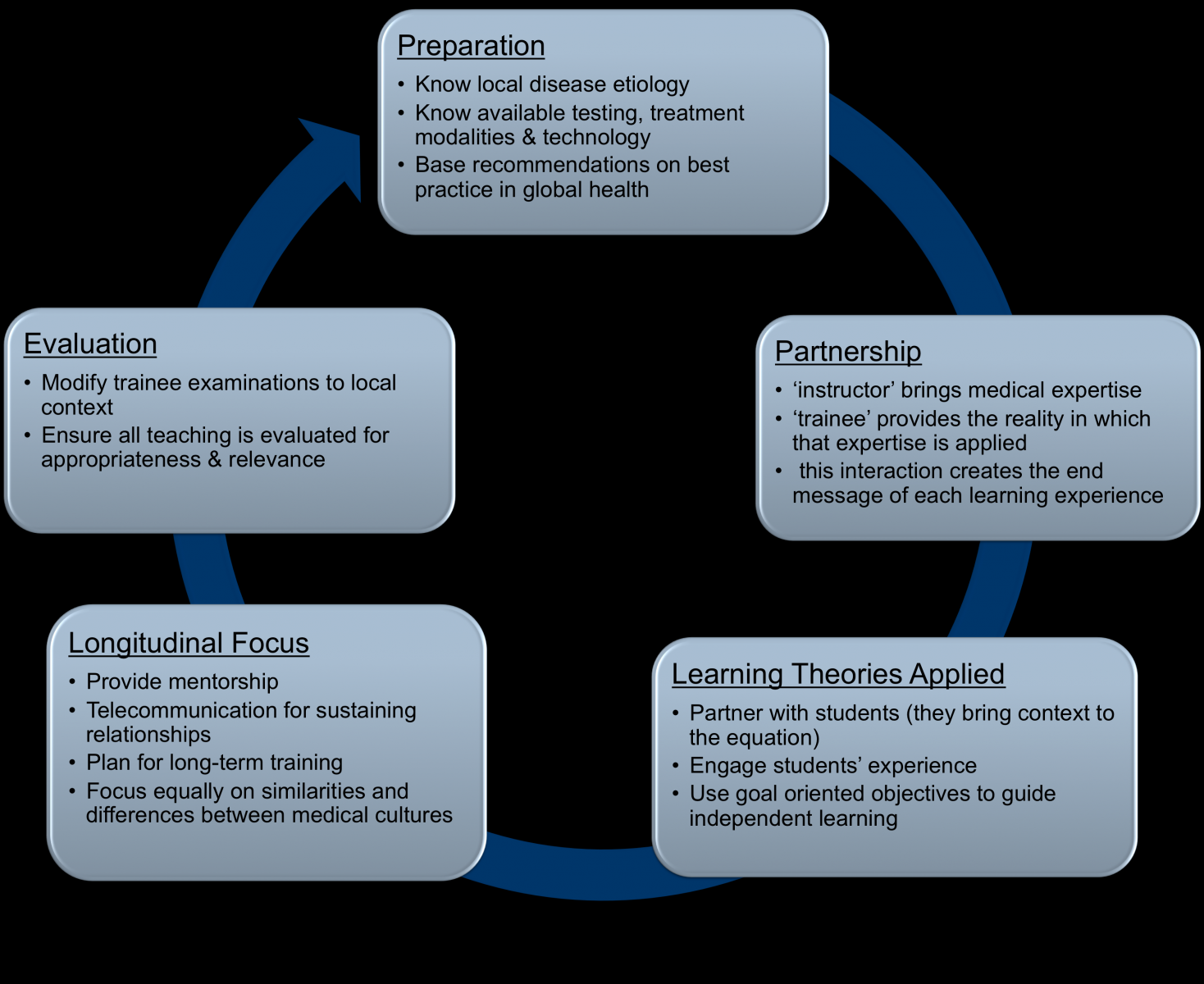

Theories of education should be modified when applied in global health partnerships.

Using this new model can frame a process for education in resource-poor settings

This new model has the potential to act as a catalyst for a discussion in best practice for Global Health Medical Education.

Theories in Medical Education:

Medical education has a wealth of theories available that can be applied to GHMEd.

In many circumstances, teaching in RPAs occurs by preceptors from relatively resource-rich settings with different medical and social cultural settings.

There is an argument for preceptors to use the ‘diversimilarity’ paradigm, placing equal emphasis on similarities and diversity between medical cultures.

Using this technique, instructors discuss practice similarities between locations balanced with focus on divergences in practices.

Best Practice in Global Health Medical Education (GHMed):

The term GHMEd is defined as:

The process of inter-cultural educational partnerships occurring between instructors from resource-rich areas and students from resource-poor areas

Currently, the vast majority of literature related to this field focuses on ethical and educational principles for preparing health care workers from the ‘global north’ to work abroad.

There is also great work being done in education to support programs aiming to create residency streams in global health.

There is little focus, however, on how to alter our clinical practice (although to mention that we certainly should) and even less so on how to alter educational practice.

Technology Use for Teaching in Resource-Poor Settings:

The nature of many partnerships in GHMEd is that clinician educators from resource-rich settings visit companion sites for brief periods.

Helping to counter this potential lack of continuity in teaching and mentorship is the use of technologies

Send Email

Send Email