Theme

Best Practice in Student Assessment, and Feedback

INSTITUTION

Bahrain Defence Force Hospital

Teaching is a complex activity with many interrelated mechanisms, such as clarity, interaction, organization, enthusiasm, and feedback. It is well established that teaching quality is highly effective on student achievement in both general and medical teaching settings, and is thus very important. Therefore, providing appropriate teaching tools to improve teaching quality should be of high importance. One tool that has been suggested to benefit tutor improvement is feedback on tutors given by students. This tool may also be beneficial in clinical settings.

while the effects of feedback on teaching quality may seem promising, evaluating the effectiveness of teaching (giving feedback) is difficult in a complex clinical setup in contrast to controlled environments such as classrooms, seminars and laboratories [14]. Thus, it is possible to expect that some difficulty could be encountered when implementing this tool in clinical settings.

It is important to understand whether feedback is effective in clinical settings in other cultures. Feedback can be quite challenging in the Middle East due to the culture of hierarchy in medicine that normally involves a one-way information flow from tutor to student rather than a two-way discussion.

This study aims to identify the effect of student feedback on teaching quality improvement of medical tutors in the Middle East.

Method

Participants:

•57 Clinical Tutors (70.2% male, 29.8% female)

•1 196 Undergraduate medical students (61.2% female, 38.8% male) from The Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland-Bahrain.

•The tutors were from different departments including surgery, medicine, psychiatry, paediatrics, obstetrics and gynaecology, and pathology.

Among these clinical tutors 60% of them were Bahraini and the rest came from several different backgrounds.

Materials

•The mSETQ is used in this study as the feedback questionnaire.

•This questionnaire consists of 25 items divided into 6 different subscales. Each subscale involves a set of statements in which participants indicate the extent to which they agree with the statements using a 5-point likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”.

•The subscales are, teaching and learning environment, professional attitude towards students, goal communication, student evaluation, feedback, and promoting self directed learning.

Design

•The study uses a repeated measure longitudinal design measured at two different time points with a six-month interval.

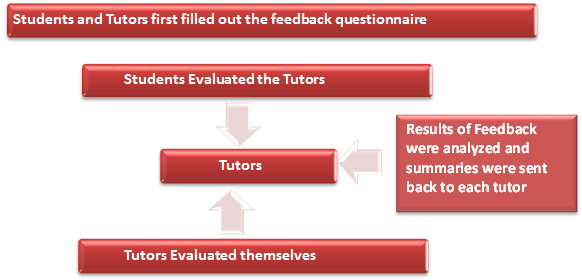

Procedure

Then the clinical tutors were asked to,

•Reflect on the received student feedback

•immediately design strategies for themselves

•improve their teaching based on the student feedback.

•The self-evaluation was also part of the reflecting process because it will allow the tutors to see the differences between their teaching quality perceived by them and by the students.

•The second evaluation was completed after a period of six months by the students for the same clinical tutors.

Results

Average teaching quality of the clinical tutors:

To assess the average teaching quality of the tutors used in the study,

•cut off points were provided based on the first quartile in which any score below them was considered at risk and in need to improvement.

•The overall cutoff point for the tutors is 3.85.

•The cutoff points for each subscale were, 3.92 for teaching and learning environment, 3.79 for professional attitude toward students, 3.83 for the communication of goals, 3.74 for the evaluation of students, 3.88 for feedback, and ,3.95 for promoting self-directed learning.

•Tutors in all four of the hospitals scored above a 3.8, with a range of 4.05 - 4.31 in all subscales.

•The two highest-scoring domains across hospitals were teaching and learning environment and professionalism toward students.

• the lowest-scoring domains were the communication of goals and the evaluation of students.

Table 1 Clinical Tutors teaching quality evaluation

|

|

Scale |

|

|

||||||||||||

|

SI No |

T&L |

PA |

CG |

EVA |

FB |

PS |

Overall |

p value* |

|||||||

|

|

Y1 |

Y2 |

Y1 |

Y2 |

Y1 |

Y2 |

Y1 |

Y2 |

Y1 |

Y2 |

Y1 |

Y2 |

Y1 |

Y2 |

|

|

D1 |

3.92 |

3.97 |

3.96 |

4.24 |

3.78 |

3.96 |

3.75 |

3.91 |

3.73 |

3.76 |

3.64 |

4 |

3.82±0.84 |

4.13±0.51 |

0.275 |

|

D2 |

3.51 |

3.51 |

3.76 |

3.47 |

3.44 |

3.27 |

3.58 |

3.60 |

3.63 |

3.57 |

3.47 |

3.51 |

3.61±0.56 |

3.51±0.85 |

0.745 |

|

D3 |

4.42 |

4.64 |

4.59 |

4.75 |

4.12 |

4.22 |

4.50 |

4.25 |

4.48 |

4.25 |

4.39 |

4.59 |

4.39±0.72 |

4.38±0.52 |

0.967 |

|

D4 |

4.11 |

4.78 |

4.18 |

4.67 |

4.00 |

4.53 |

4.26 |

4.53 |

4.04 |

4.42 |

3.90 |

4.36 |

4.08±0.94 |

4.61±0.69 |

0.185 |

|

D5 |

4.57 |

4.04 |

4.65 |

4.28 |

4.53 |

3.91 |

4.55 |

4.05 |

4.78 |

4.20 |

4.60 |

4.24 |

4.58±0.64 |

3.66±0.98 |

0.019 |

|

D6 |

4.83 |

4.81 |

4.94 |

4.59 |

4.79 |

4.75 |

4.85 |

4.39 |

4.78 |

4.58 |

4.79 |

4.65 |

4.83±0.27 |

4.8±0.26 |

0.834 |

|

D7 |

3.89 |

3.85 |

3.44 |

3.78 |

3.76 |

4.05 |

3.87 |

3.90 |

3.98 |

4.10 |

3.98 |

3.99 |

3.78±0.95 |

3.83±0.75 |

0.877 |

|

D8 |

3.11 |

3.50 |

2.48 |

3.38 |

3.12 |

3.35 |

2.77 |

3.45 |

2.77 |

3.41 |

3.53 |

3.9 |

2.9±0.88 |

3.26±1.05 |

0.339 |

|

D9 |

4.09 |

4.56 |

4.13 |

4.44 |

4.07 |

4.33 |

4.32 |

4.38 |

4.22 |

4.23 |

4.18 |

4.06 |

4.16±1.09 |

4.33±0.70 |

0.641 |

|

D10 |

4.48 |

3.40 |

4.54 |

2.80 |

4.58 |

3.80 |

4.44 |

3.80 |

4.53 |

2.80 |

4.65 |

4 |

4.33±0.93 |

3.43±0.15 |

0.084 |

Table 2. Average feedback scores in time one and time two.

|

|

Number of clinical tutors |

Overall mean score |

Scale |

|||||

|

Teaching and Learning |

Professional attitude |

Communication goals |

Evaluation |

Feedback |

Promoting self-directed learning |

|||

|

Time 1 |

57 |

4.28±0.82 |

4.32±0.84 |

4.37±0.86 |

4.22±0.95 |

4.24±0.89 |

4.25±0.89 |

4.31±0.88 |

|

Time 2 |

57 |

4.21±0.79 |

4.24±0.86 |

4.24±0.89 |

4.16±0.94 |

4.18±0.84 |

4.20±0.91 |

4.28±0.86 |

|

p- value |

|

0.12 |

0.06 |

<0.001* |

0.28

|

0.14 |

0.29 |

0.59 |

*p<0.05 statistically significant. Data expressed as mean± SD.

Effects of feedback on teaching quality

•A paired samples t-test revealed no significant difference in the overall mean scores of the scales assessed in time one (4.28 ± 0.82) and time two (4.21 ± 0.79), (0.067, p = 0.12).

•However when looking at differences across time points within each scale, the professional attitude factor showed a statistically significant decrease with a mean difference of 0.13 (p <0.001).

•Further investigation suggested a pattern in changes of scores across time points for different tutors. Tutors (N=16) with overall mean scores <4.0 at time one demonstrated an improvement in their overall mean scores at time two (from 3.53±0.35 to 3.84±0.51, p <0.01).

•On the other hand, the 18 tutors with overall mean scores > 4.5 at time one exhibited a deterioration of their overall mean scores at time two (from 4.73±0.13 to 4.28±0.52, p <0.01).

Table 3. Comparison of changes in the overall score

|

|

Number of clinical tutors |

Mean overall score |

P value |

|

|

Time 1 |

Time 2 |

|||

|

Mean overall score <4.0 |

16 |

3.53±0.35 |

3.84±0.51 |

<0.01* |

|

Mean overall score 4.0-4.50 |

23 |

4.26±0.15 |

4.26±0.30 |

0.91 |

|

Mean overall score > 4.5 |

18 |

4.73±0.13 |

4.28±0.52 |

<0.01* |

*p<0.05; statistical significance

Discussion

In order to understand the effects of student feedback on the teaching quality of clinical tutors, the study investigated the effect of students’ evaluation of their tutors and a reflection of this evaluation by the tutors.The study hypothesized that the feedback strategy will lead to an improvement in student-perceived teaching quality of clinical tutors. Contrary to the hypothesis and to previous findings this study demonstrated no overall increase in perceived teaching quality after receiving feedback. An unexpected a possible pattern in the mean results suggested a positive effect of feedback only in those with an initially inferior teaching quality, but not others. Those with high initial performance demonstrated a decrease in teaching quality after feedback The study showed that most of the tutors in the experiment had an overall good student-perceived quality of teaching. The gender of the students did not affect their ratings. The level of student education did have different feedback responses only in time one.

The effect of student level on ratings could have possibly dropped n the second year to the increase in number of participants.The finding that feedback did not improve overall teaching quality in all the tutors may have been due to some limitations, which if improved could have possibly provided different results. One possible limitation in this study is that the questionnaire was entirely student centered, improving the feedback strategy interventions could provide better enhancement for teaching qualities. Effectively enhancing teaching quality could benefit both from student and teacher evaluation. Despite the evidence suggesting the positive effect of feedback on teaching quality, the type of feedback and the way it is given influences the effect it has on teaching quality .Implementing a face-to-face feedback strategy could provide more effective results and lead to more accurate results demonstrating the effect of feedback.

Overall, this study suggests that student feedback strategies do not improve the overall teaching quality in all the clinical tutors, but only those with initial inferior teaching performance. The study further demonstrates the importance of studying this topic and suggests that the effectiveness of a feedback strategy can be more complex than straightforward, by showing that some tutors benefited from it whereas others did not. further suggest the possibility for this tool to be beneficial when the best conditions for its effectiveness are identified and met. Therefore, the findings of this study can be used to support the importance of studying and developing feedback interventions in clinical settings in the Middle East.

Student feedback did not improve the overall quality of teaching in clinical tutors in the Middle East. The findings suggest that applying such a strategy to improve teaching quality is more complex and several other factors may mediate the effectiveness of student feedback such as culture and differences in competence of tutors.

[1] Aaronson, Daniel, Lisa Barrow, and William Sander. 2007. "Teachers And Student Achievement In The Chicago Public High Schools". Journal Of Labor Economics 25 (1): 95-135. doi:10.1086/508733.

[2] Marsh, Herbert W., and Lawrence Roche. 1993. "The Use Of Students' Evaluations And An Individually Structured Intervention To Enhance University Teaching Effectiveness". American Educational Research Journal 30(1): 217. doi:10.2307/1163195

[3] Gould, B., Grey, M., Huntington, C., Gruman, C., Rosen, J., & Storey, E. et al. (2002). Improving Patient Care Outcomes by Teaching Quality Improvement to Medical Students in Community-based Practices. Academic Medicine, 77(10), 1011-1018. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200210000-00014

[4] Rivkin, S., Hanushek, E., & Kain, J. (2005). Teachers, Schools, and Academic Achievement. Econometrica, 73(2), 417-458. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0262.2005.00584.x

[5] Rockoff, J. (2004). The Impact of Individual Teachers on Student Achievement: Evidence from Panel Data. American Economic Review, 94(2), 247-252. http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/0002828041302244

[6] Baker, K. (2010). Clinical Teaching Improves with Resident Evaluation and Feedback. Anesthesiology, 1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/aln.0b013e3181eaacf4

[7] Bok, H., Teunissen, P., Spruijt, A., Fokkema, J., van Beukelen, P., Jaarsma, D., & van der Vleuten, C. (2013). Clarifying students’ feedback-seeking behaviour in clinical clerkships. Medical Education, 47(3), 282-291. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/medu.12054

[8] Branch, W., & Paranjape, A. (2002). Feedback and Reflection. Academic Medicine, 77(12, Part 1), 1185-1188. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200212000-00005

[9] Stalmeijer, R., Dolmans, D., Wolfhagen, I., Peters, W., van Coppenolle, L., & Scherpbier, A. (2009). Combined student ratings and self-assessment provide useful feedback for clinical teachers. Advances In Health Sciences Education, 15(3), 315-328. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10459-009-9199-6

[10] Kember, D., Leung, D., & Kwan, K. (2002). Does the Use of Student Feedback Questionnaires Improve the Overall Quality of Teaching?. Assessment & Evaluation In Higher Education, 27(5), 411-425. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0260293022000009294

[11] Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The Power of Feedback. Review Of Educational Research, 77(1), 81-112. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

[12] Clynes, Mary P., and Sara E.C. Raftery. 2008. "Feedback: An Essential Element Of Student Learning In Clinical Practice". Nurse Education In Practice 8 (6): 405-411. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2008.02.003.

[13] Telio, S., Ajjawi, R., & Regehr, G. (2015). The “Educational Alliance” as a Framework for Reconceptualizing Feedback in Medical Education. Academic Medicine, 90(5), 609-614. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000560

[14] Skeff, K. (1988). Enhancing teaching effectiveness and vitality in the ambulatory setting. Journal Of General Internal Medicine, 3(S1), S26-S33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/bf02600249

Send Email

Send Email