|

Authors | Institution |

|

Yuka Urushibara-MIYACHI Toru Kamiya Daien Oshita Miho Iwakuma Hiroshi Nishigori |

Kyoto University - Center for Medical Education - Kyoto - Japan Rakuwakai Otowa Hospital - Department of Infectious Diseases and Department of General Internal Medicine - Kyoto - Japan Department of Medical Communication, Kyoto University, School of Public Health, Kyoto, Japan |

|

|

||||||

| Considering how healthcare professionals should talk about dying in clinical settings |

● Healthcare professionals feel discomfort in discussing death with dying patients from various reasons. (Bernacki and Block, 2014; You, 2015)

- Discomfort to talk about death

- Unable to respond to strong negative feelings from patients and family members evoked by the discussion

- Fear for depriving hope from patients by telling truth

- …

● It also has been regarded as taboo to talk about death in healthcare settings for a long time.

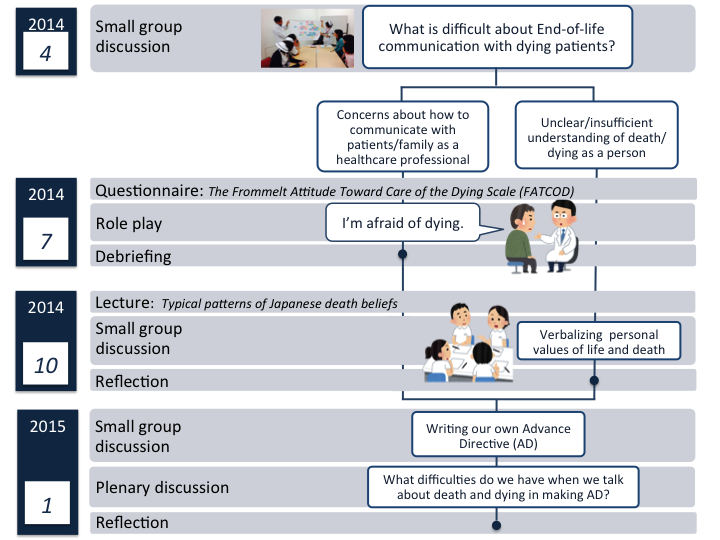

● We implemented four off-the-job sessions in which participants discussed how they faced with dying patients in a community-based hospital in Japan.

● Aim of the sessions

To provide opportunities for healthcare professionals to discuss how we should talk about dying with patients

● Structure of the sessions

1) Discussing difficulties in end-of-life communication in small groups

2) Role playing about talking on death with patients who say…

“I want to die.” ”Kill me.”

“I’m afraid of dying. ”

“What will happen after I die?”

3) Discussing personal values of life and death in small groups

4) Writing their own Advance Directive (AD)

● Evaluation

- The Frommelt Attitude Toward Care of the Dying scale, Form B, Japanese version (FATCOD-Form B-J) (Nakai, et al., 2006)

- Paper-based questionnaires after each session

Fig 1. Members of the plannning group and participants

Fig 2. Structure of the sessions

1) Bernacki, R. E., & Block, S. D. (2014). Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA internal medicine, 174(12), 1994-2003.

2) You, J. J., Downar, J., Fowler, R. A., Lamontagne, F., Ma, I. W., Jayaraman, D., ... & Heyland, D. K. (2015). Barriers to Goals of Care Discussions With Seriously Ill Hospitalized Patients and Their Families: A Multicenter Survey of Clinicians. JAMA internal medicine.

3) Nakai, Y., Miyashita, M., Sasahara, T., Koyama, Y., Shimizu, Y., & Kawa, M. (2006). Factor structure and reliability of the Japanese version of the Frommelt attitudes toward care of the dying scale (FATCOD-BJ). Jpn J Cancer Nurs,11(6), 723-729.

4) Bito, S., Matsumura, S., Singer, M. K., Meredith, L. S., Fukuhara, S., & Wenger, N. S. (2007). ACCULTURATION AND END-OF-LIFE DECISION MAKING: COMPARISON OF JAPANESE AND JAPANESE-AMERICAN FOCUS GROUPS. Bioethics, 21(5), 251-262.

5) Voltz, R., Akabayashi, A., Reese, C., Ohi, G., & Sass, H. M. (1998). End-of-life decisions and advance directives in palliative care: a cross-cultural survey of patients and health-care professionals. Journal of pain and symptom management, 16(3), 153-162.

6) Sam, D. L., & Berry, J. W. (2010). Acculturation when individuals and groups of different cultural backgrounds meet. Perspectives on Psychological Science,5(4), 472-481.

7) Davis, A. J., Konishi, E., & Mitoh, T. (2002). The telling and knowing of dying: philosophical bases for hospice care in Japan. International nursing review,49(4), 226-233.

● Approximately 30 multi-professional participants joined in each session.

● From the analysis of FATCOD, the lowest average score was found on the item 3 (M=3.00, SD=0.26; i.e., “I would be uncomfortable talking about impending death with the dying person’’).

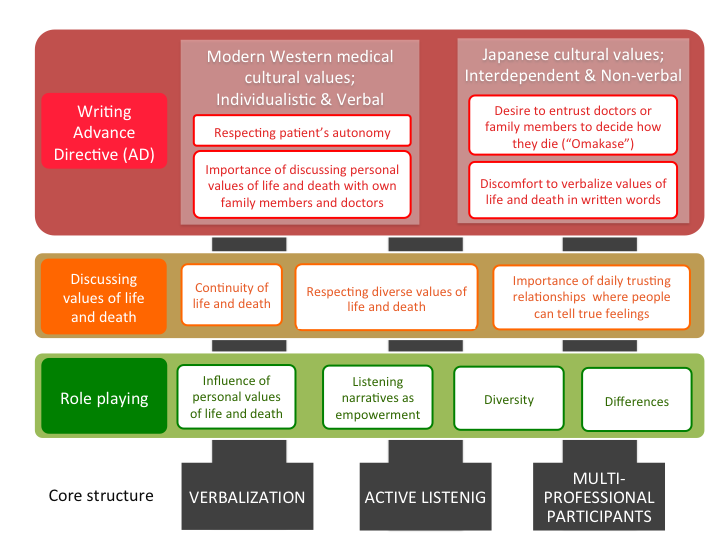

● From the evaluation, we found participants learned the importance of listening to patients’ narratives and respecting diverse values of life and death.

● In writing AD, some wanted doctors or family members to decide how they die, and others felt discomfort to verbalize it in written words.

Fig 3. Overview of the themes from questionairres and narratives during discussions

Discussion

● Japanese cultural values for communication

1) Non-verbal communication, expecting intimate others to read between lines

- Japanese saw written directives as intrusive (Bito et al. 2007)

2) Decision making system has been interdependent rather than individualistic

- Entrusting all decisions to the family or physicians (known as Omakase) (Voltz et al. 1998)

● Modern western medical culture may promote healthcare professionals to value patient autonomy with formal signed documents.

● Various attitudes among healthcare professionals regarding talking about death and making advance directives can be explained by acculturation strategies (Berry and Sam, 2010)

- Integration of Western medical cultures in Japan as a non-Western country

- Conflict among two cultures; assimilation or separation

Conclusion

● The effectiveness of our session may be controversial.

● Further investigation may be needed how Japanese healthcare professionals can strategically “acculturate” Western modern medicine.

Japanese healthcare professionals may be westernized and modernized when they play roles as healthcare professionals, besides they preserve Japanese traditional culture when they consider dying as patients. Inner discrepancy should be further researched.

Send Email

Send Email