|

Authors | Institution |

|

Noriyuki Takahashi Muneyoshi Aomatsu Takuya Saiki Takashi Otani Nobutaro Ban |

Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, Department of General Medicine, Nagoya, Japan Gifu University, Medical Education Development Center, Gifu, Japan Department of Educational Sciences, Graduate School of Education and Human Development, Nagoya Univ |

|

|

||||||

| Exploring the effect of using real patients cases in peer role-play in undergraduate medical interview education: a qualitative study |

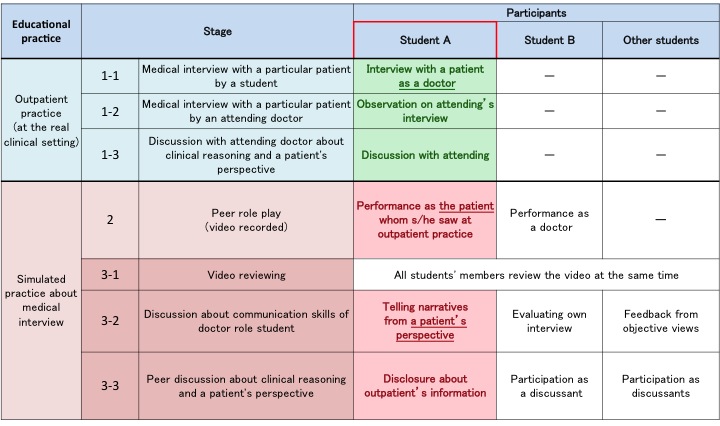

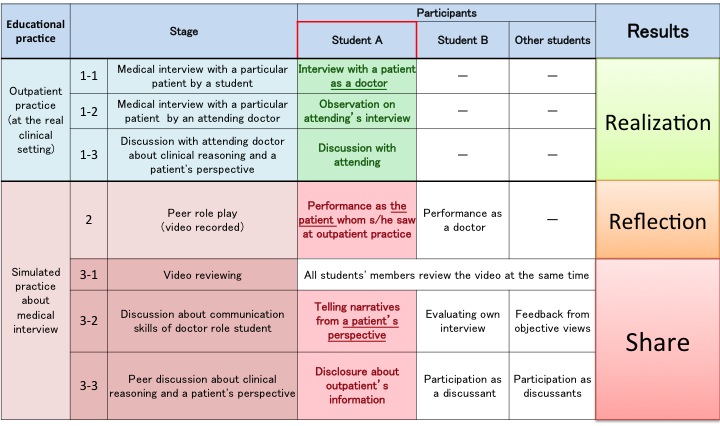

Although reality is important for communication skills training in undergraduate clinical education1), a peer role-play generally uses scenarios which have the limitation of reality2). The aim of this study is to explore how the real patients’ cases with whom medical students encountered in outpatient clinical clerkship affect a peer role-play to learn patients’ perspectives.

We conducted two half-days of medical interview skills trainings for the 5th year medical students during their clinical rotation at Nagoya university department of General Medicine. This program consisted of three stages: medical interview in outpatient practice, peer role-play and group discussion. We conducted twelve focus groups after the training session and 63 medical students participated in it from 2012-2013. The transcripts of the focus groups were analyzed qualitative analytical method named "Steps for Coding and Theorization" (see more detail). The Ethical Committee of Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine approved this study (2012-0027).

Table 1. Details of this program

The process of understanding patients’ perspectives

Phase 1. Realization about patients' “unexpected narratives”

Students realized patients' “unexpected narratives” through an interview with a particular patient and discussion with attending doctor in out patient practice. Because patients’ perspectives hid or explained or connected with unexpectedly from the viewpoints of students, they found patients’ perspectives as unexpectedness. The realization of “unexpected narratives” let them understand that patients’ perspectives gave meanings by patients’ contexts without relating to medical knowledge. These students’ understandings are considered from the grasp about patients’ individuality and variety, which real patients take a crucial part of learning3).

Phase 2. Reflection about patients’ “unexpected narratives”

Patient-role students had opportunities to reproduce patients’ “unexpected narratives” in peer role-play. This reproduction let them reflect on relations of patients’ perspectives to contexts. Role-play suggests promoting the refleciton4). Doctor-role students recognized patients’ “unexpected narratives” as a character of patients.

Phase 3. Share about patients’ “unexpected narratives”

Through a discussion, audience shared patients’ “unexpected narratives” by two factors. First, clinical reasoning of a particular patient caused the share of “unexpected narratives” as the authenticity in case based learning5). Second, voluntary disclosure by patient-role students about the reflection of “unexpected narratives” caused to share the narratives accompanied by a stimulation of students’ emotional empathy6).

Figure 2. The process of understanding patients’ perspectives

Real cases with whom medical students encounter in outpatient clinical clerkship affect students in a peer role-play and discussion to reflect and share the individuality and variety of patients' perspectives, which real patients take a crucial part to learn.

Using real cases help students’ reflection and share the understanding about the individuality and variety of patients' perspectives. Similar teaching methods will also be applicable in postgraduate education.

This study was funded by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research awarded by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Grant Number 24659239, 2012/4-2015/3

1) McGaghie, William C., et al. "A critical review of simulation‐based medical education research: 2003–2009." Medical education 44.1 (2010): 50-63.

2) Kurtz, S. M., et al. "Teaching and learning communication skills in medicine." Oxford: Radcliffe Pub. (2005).

3) Spencer, John, et al. "Patient-oriented learning: a review of the role of the patient in the education of medical students." Medical education 34.10 (2000): 851-857.

4) Clapper, T. "Role play and simulation." Education Digest 75.8 (2010): 39-43.

5) Thistlethwaite, Jill Elizabeth, et al. "The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education. A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 23." Medical teacher 34.6 (2012): e421-e444.

6) Aomatsu, Muneyoshi, et al. "Medical students' and residents' conceptual structure of empathy: a qualitative study." Education for Health 26.1 (2013): 4.

Send Email

Send Email