Theme

3BB The lecture and the flipped classroom

Title

Evaluating the Impact of the Flipped Anatomy Classroom: What is the Correct Outcome?

Background

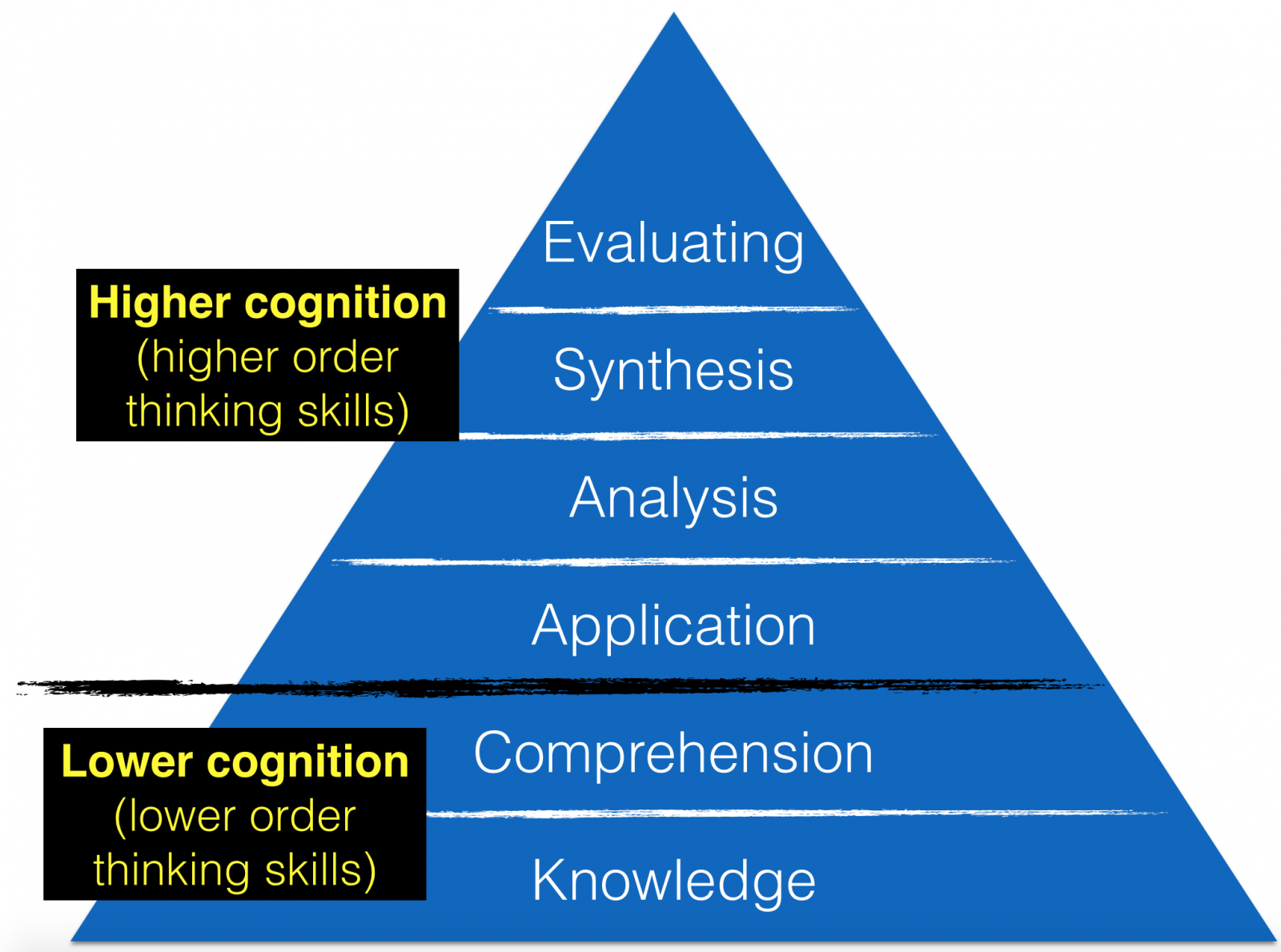

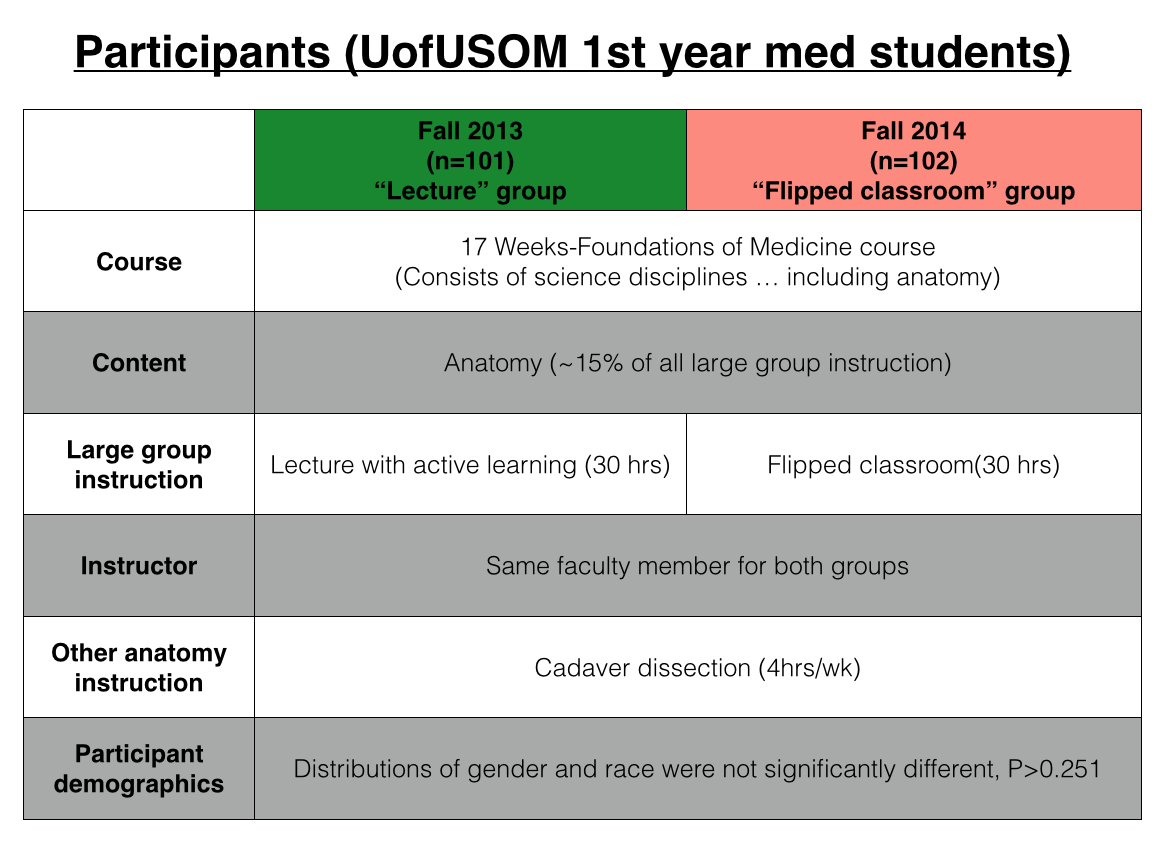

- Based upon principles of active learning the Flipped Classroom (FC) method of teaching should lead to better retention, understanding and problem solving at a higher cognitive level.1,2,3

- However, research results are mixed.

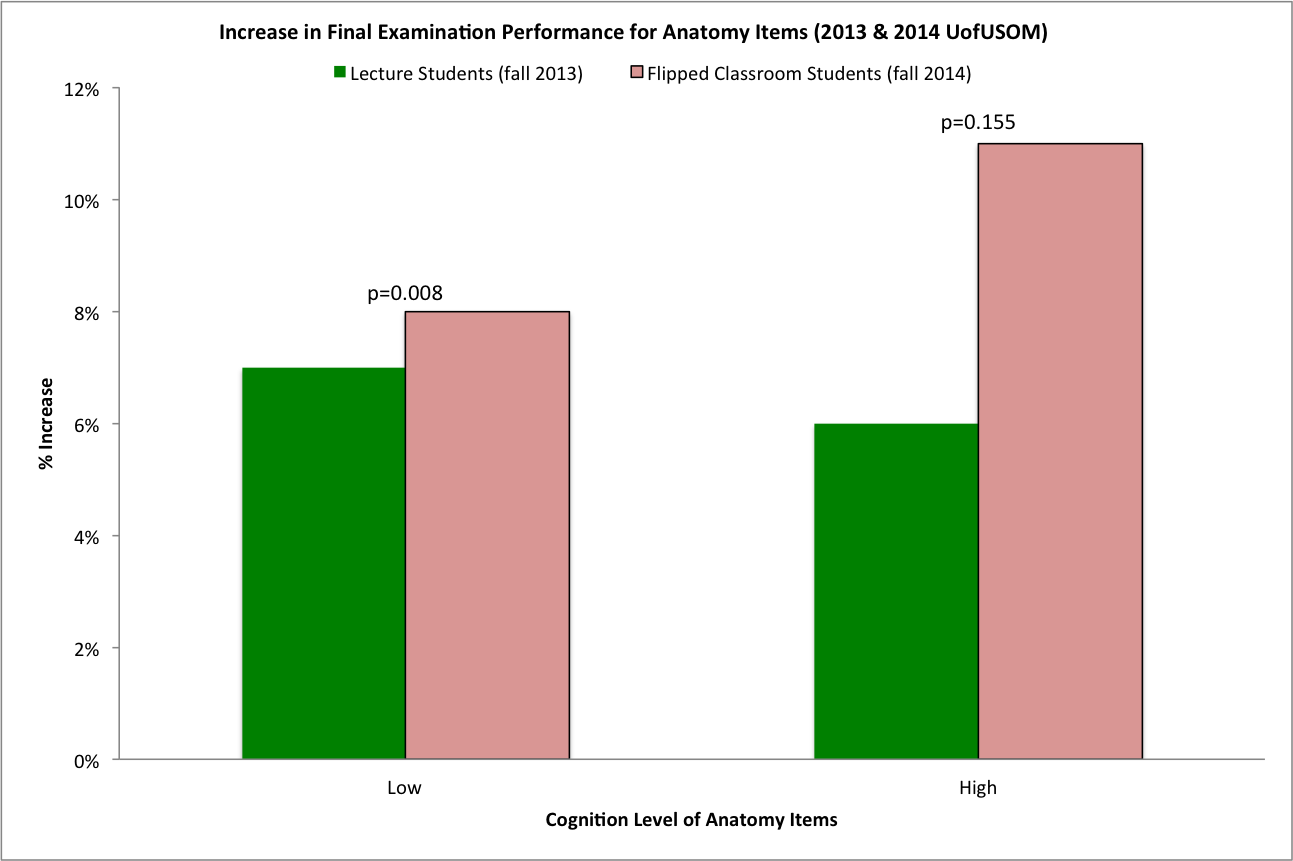

- One reason for the mixed results may be the cognitive level assessed. The FC is designed to promote higher cognitive levels (e.g. application) so a lower level assessment (e.g. recall) may not be an appropriate outcome for the FC.

4

4

- Hypothesis. FC students would perform better than lecture students on an assessment requiring higher cognition and there would be no difference in performance for an assessment requiring lower cognition.

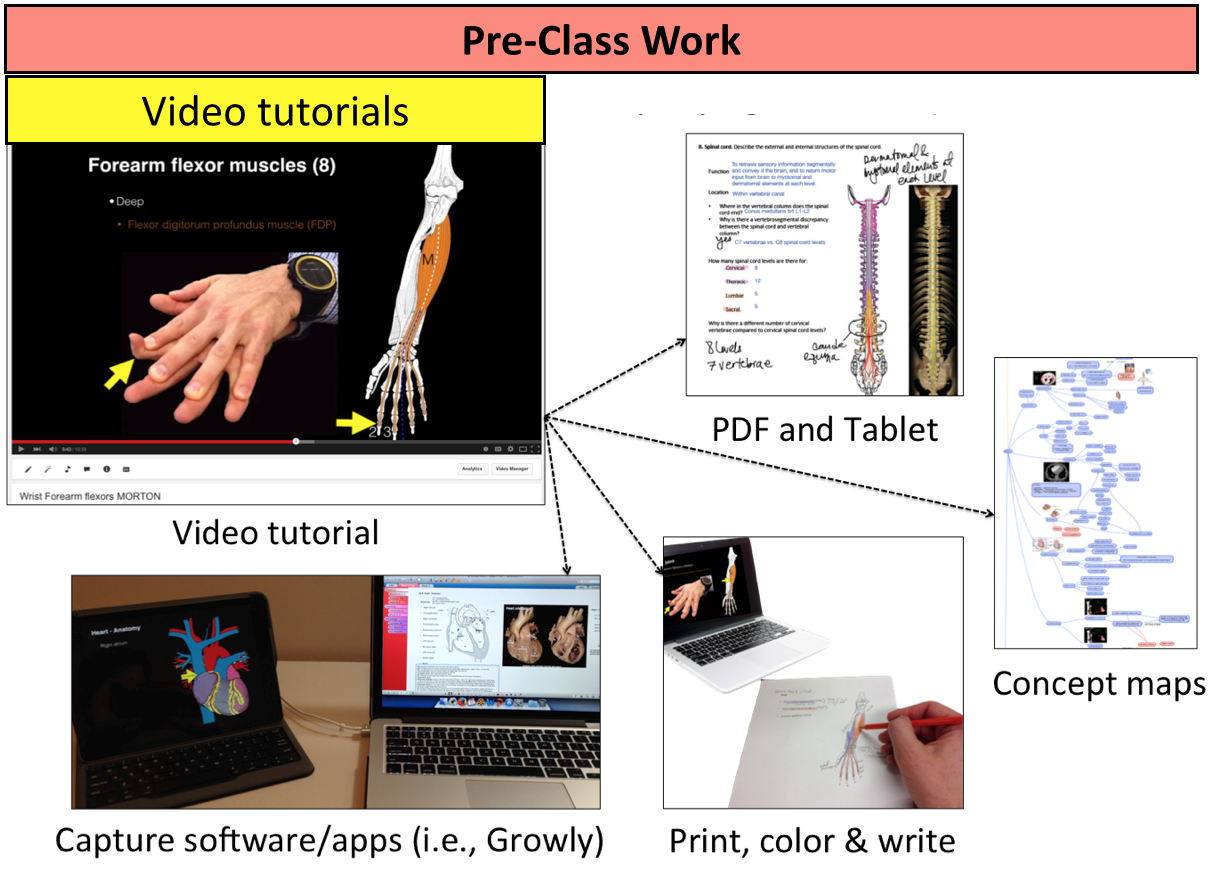

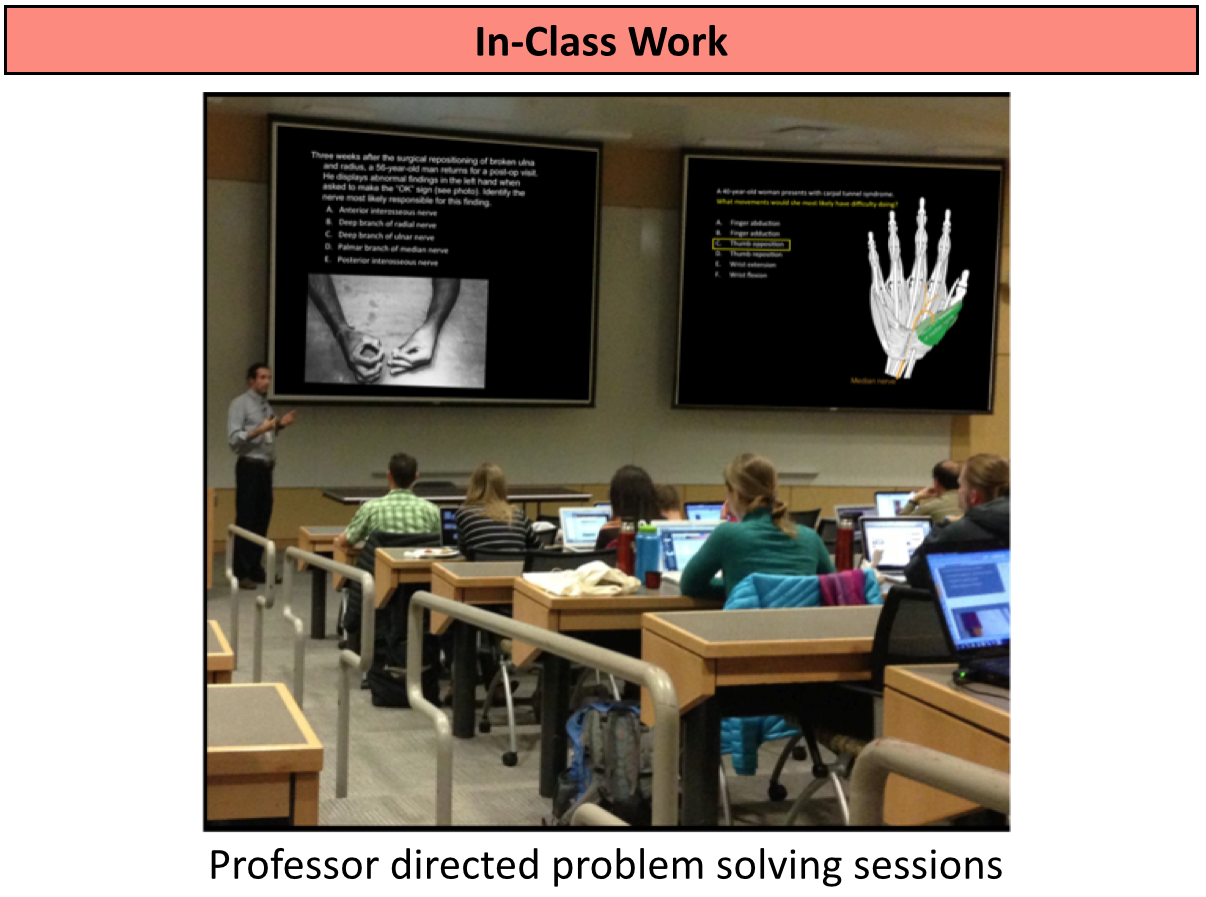

- FC content followed this pattern for each large classroom session:

- Students completed a summative exam on all course topics, including Anatomy.

Summary of Results

- Retention: 150-item multiple choice final examination where items were catagorized as requiring lower or higher cognition according to Bloom's taxonomy.

- Lower cognition and higher cognition means were compared between lecture and FC groups using Mann-Whitney U tests.

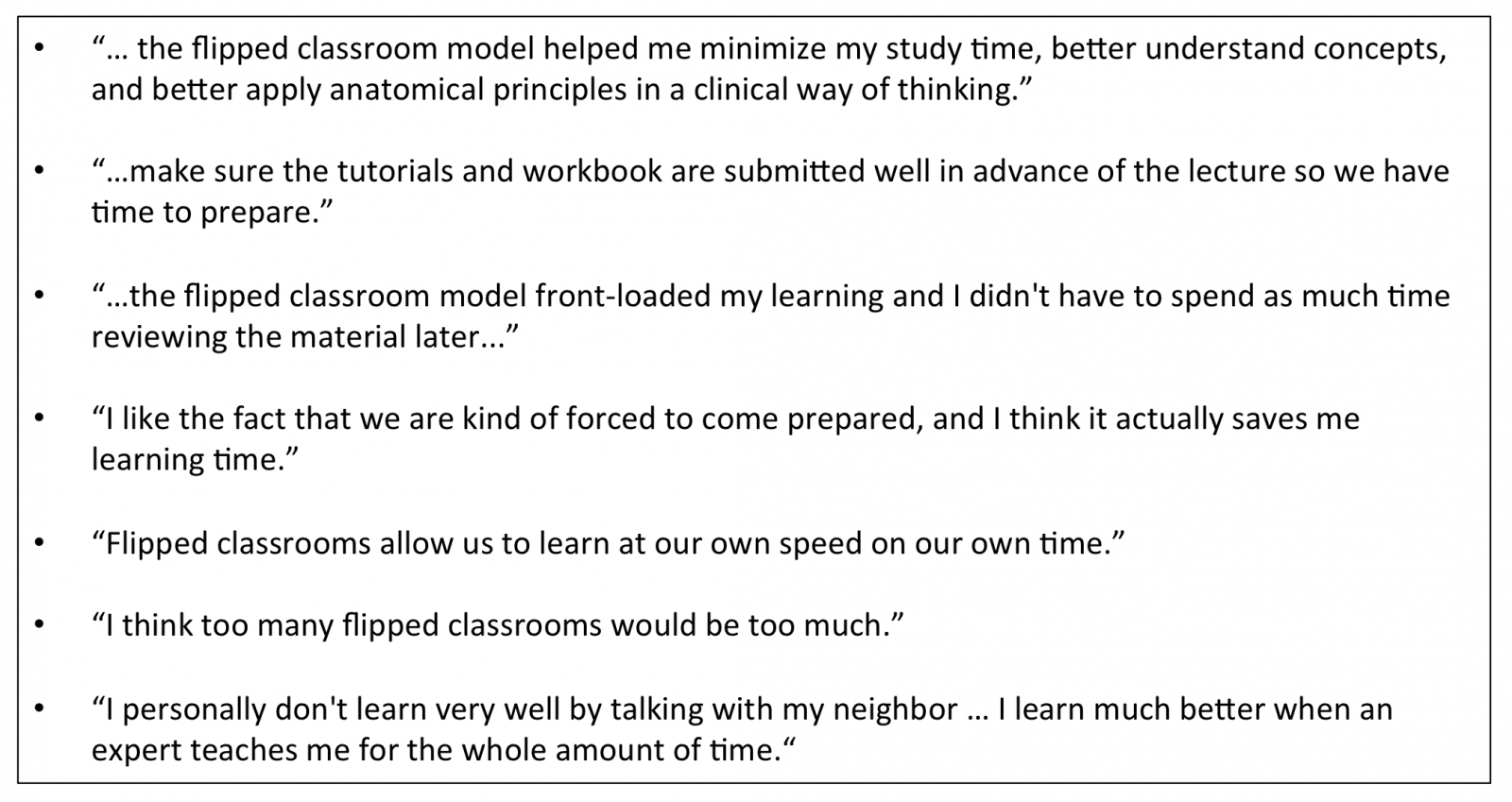

- Sample of qualitative feedback from students participating in the FC model:

Take-home Messages

If research regarding the FC method uses student learning as a basis for effectiveness and the assessment of student learning only requires a low level of cognition we will not fully understand the potential benefit of the FC.

Acknowledgement

- Sections of this paper were presented at the April 2015 Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC)’s Western Groups of Education Affairs conference in San Diego, CA.

- A special thanks to John Bell and William Bradshaw from Brigham Young University for their support and guidance over the years in this project.

References

- McLaughlin JE, Roth MT, Glatt DM, Gharkholonarehe N, Davidson CA, Griffin LM, Esserman DA, Munper RJ. The flipped classroom: A course redesign to foster learning and engagement in a health processions school. Acad Med. 2014; 89: 236-43.

- Lape NK, Levy R. Probing the inverted classroom: a controlled study of teaching and learning outcomes in undergraduate engineering and mathematics. ASEE National Conference Proceedings, Indianapolis, IN. 2014.

- Missildine K, Fountain R, Summers L, Gosselin K. Flipping the classroom to improve student performance and satisfaction. J Nurs Educ. 2013;52:597-599.

- Bloom BS, Engelhart MD, Furst EJ, Hill WH, Krathwohl DR. Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. 1956. New York: David McKay Company.