| Theme: 3AA Mobile learning and social networks | |||

|

||||||

| Improving Access to Stakeholder Input in Distributive Educational Programs Using Social Media Platforms: A Qualitative Study |

|

|||||

|

||||||

Professional social networks can be effectively utilized to obtaining valuable stakeholder curricular engagement, but continuous monitoring and frequent prompting are necessary to ensure full participation.

At institutions utilizing a distributed educational model, face-to-face engagement with key stakeholders is a challenge. This study explored the feasibility of using a social media platform designed for professional networking (LinkedIn) as a way for conducting asynchronous focus groups; thus, facilitating and enhancing distant faculty engagement in curricular relevant issues and decisions.

Population: Preceptors involved in clinical teaching of students in their 3rd or 4th year of veterinary curricula were asked to participate in a focus group to explore topics for preceptor professional development. Participants were not asked a preference for online or face-to-face focus groups. For the LinkedIn groups, participants were asked to create a LinkedIn profile if they did not already have one. One moderator was the primary moderator in each group allowing the other to observe the interactions. One group (n=5) participated in the 2-hour, face-to-face facilitated focus group. Two groups (n=8, 6) participated in an asynchronous facilitated focus groups on LinkedIn.

Interview Questions: Semi-structured interview questions were employed in both face-to-face and online focus groups. These questions focused on experiences, thoughts, and impressions regarding student teaching in non-academic clinical settings and what professional development opportunities are needed for a veterinarian’s career growth and development. Questions were designed to align with Boyer’s four areas of Scholarship (Application, Discovery, Integration, and Teaching). If needed, questions were reworded from the face-to-face format to the social media platform to incorporate the less conversational nature of the online format. However, the focus of the question did not change between formats.

Face-to-Face Format: Preceptors attended a 2-hour session on campus, which included a complementary lunch. Two session moderators were from the university Office of Institutional Research and Effectiveness. The session was recorded for transcription and review by authors.

Social Media Platform: LinkedIn was chosen over other social media platforms (e.g., Twitter, Facebook, etc.) because of the professional networking aspect of the site. The investigators were interested in a format that would promote the professional nature of the participants and minimize the need for adjustments to security settings to provide confidentiality of the group. The LinkedIn groups were private groups open only to the participants and two moderators.

Procedure for Social Media Platform: Questions were posted one at a time with asynchronous participation from preceptors. Once conversation on a particular topic appeared to be complete (no new participation, even after moderator prompting), the next question was posted. Initial plans for posting were to allow for 2-3 days of conversation before posting of new questions. This method was chosen by the investigators to ensure that each question was explored fully and not skipped over in favor of another, more palatable or appealing question.

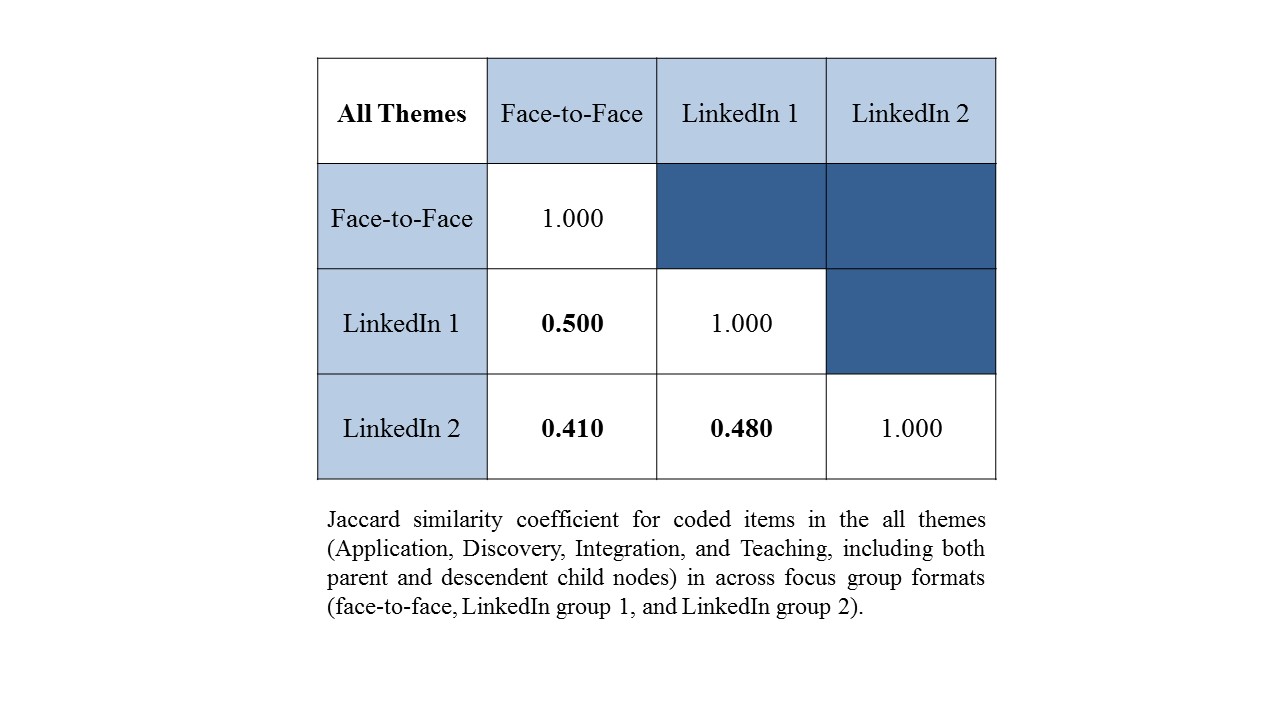

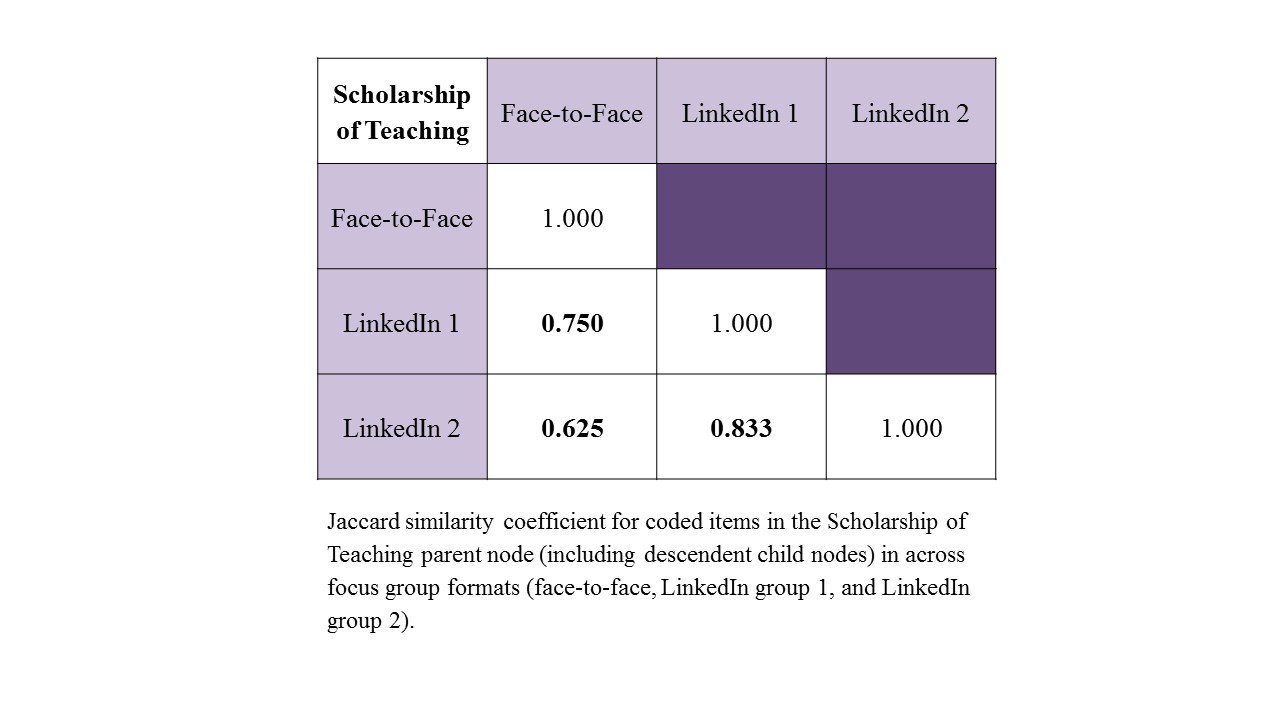

Data Analysis: Deductive thematic coding was performed on all focus group transcripts by the three authors using Boyer’s four areas of scholarship as the theoretical framework (Scholarship of Application, Integration, Discovery, and Teaching). Inductive coding was used to capture non-framework themes. Inter-rater agreement of individual coders across twenty-three parent and child nodes in the three focus groups was determined by kappa statistic in NVivo. Correlation of parent and child nodes across the three focus groups was determined by the Jaccard similarity coefficient in NVivo (web graphic for teaching alignment across three groups).

Both face-to-face and social media focus groups produced themes that aligned with Boyer’s framework. Between authors PLS and PGR, eighty-one percent of nodes had almost perfect agreement (kappa = 0.8-1), 4% substantial agreement (kappa = 0.6-0.8), and 13% moderate agreement (kappa 0.4-0.6). This strong interrater agreement between platforms indicates results are coded similarly regardless of platform.

Correlation of coded items in all four parent nodes (Scholarship of Application, Discovery, Integration, and Teaching) were moderate with Jaccard similarity coefficients ranging from 0.410 to 0.500. Examining items coded within the Scholarship of Teaching only, correlation was strong ranging with coefficients from 0.625 to 0.833.

Social media platforms designed for professional networking have potential to be viable alternatives for face-to-face focus groups with educators in distributed teaching programs.

Maintaining momentum in LinkedIn groups was challenging. Participation was initially robust, but began to wane as the third or fourth question is released. This is similar to what Williams found (as cited in Stewart, 2005) where momentum decreased in asynchronous online focus groups. Releasing questions simultaneously may help, but equality of participation in each question would need to be explored to ensure that each question elicits a robust and informative discussion. Increasing the number of group members may improve the volume of responses (Stewart, 2005), but would likely require equal diligence of moderators to ensure an adequate breadth of participation.

When participation from online members was robust, thematic coding of online and face-to-face focus groups correlated well. Utilizing an online, asynchronous platform allowed participation of a more geographically dispersed population, which provides for broader representation and thus, more accurate conclusions drawn from the gathered data. The online format also reduced the cost of administering a focus group by eliminating costs of food, transportation, and lodging of participants, especially those traveling from a distance.

Stewart, K. and Matthew, W. Researching online populations: the use of online focus groups for social research. Qualitative Research November 2005 5: 395-416, doi:10.1177/1468794105056916

Send Email

Send Email