Theme

7JJ The Teacher

INSTITUTION

Faculty of Medicine - Zagazig University

University of Edinburgh

The postgraduate surgical training in the Egyptian medical schools adopts the traditional apprenticeship model, (Hamdorf and Hall, 2000), (Reid et al, 2000) and (Debas et al, 2005). However, the production of proficient surgeons needs the recruitment of adequate numbers of appropriate medical graduates as well as the provision of resources to educate and train them. Among these resources is the good surgical trainer, (Collins and Gough, 2010). Postgraduate surgical trainers are the focus of this research. From surgical trainees' perspective, what makes a good surgical trainer?

This qualitative exploratory study has employed the constructivist grounded theory methodology for data collection and analysis, (Charmaz, 2011).

Individual semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted to collect data from the purposively selected sample of trainees, (Patton, 2002).

Constant comparative analysis of data was aided by NVivo 10 computer programme, (2012 QSR International Pty Ltd).

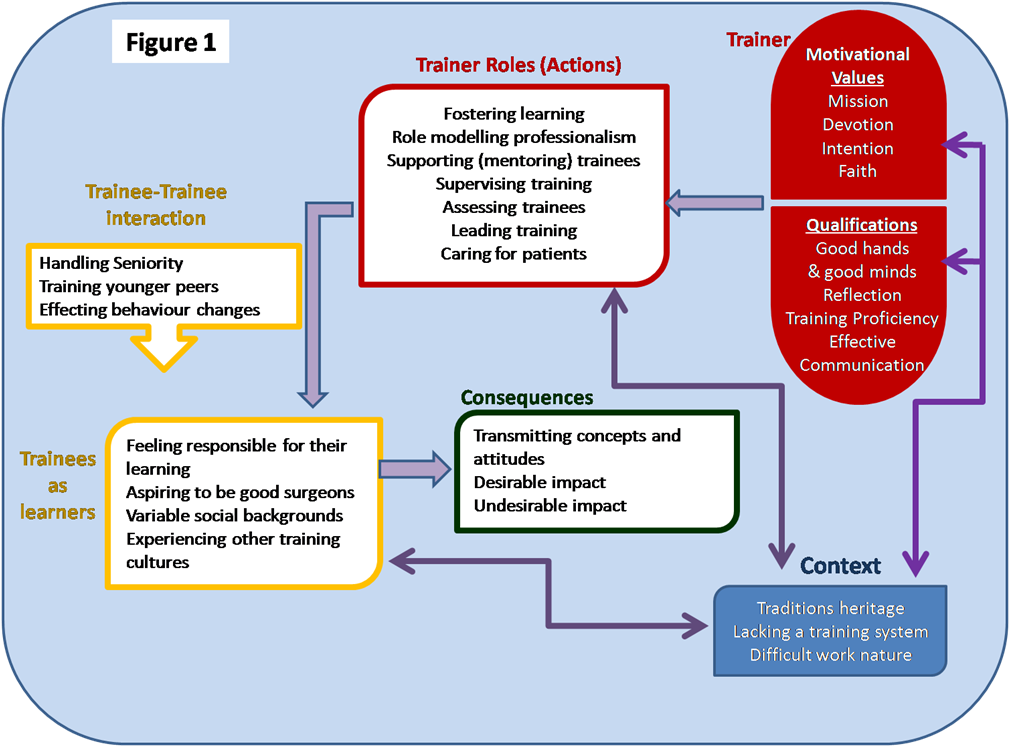

By analysis of the data presenting the participants' experiences as surgical trainees, as well as their views, thoughts and feelings about what happened and what should happen, during their training, the researcher arrived at the findings summarised in the illustrative model below (Figure 1).

After exploring surgical trainees' experiences with, and expectations of good surgical trainer in a medical school in Egypt, the researcher theorized that a good surgical trainer needs a set of qualifications and motivational values to fulfil his/her roles and provide better training experience.

The understanding of the trainees' expectations of the surgical trainer should inform the improvement endeavours of the surgical training programme as well as professional faculty development programmes. The surgical trainers' awareness of the trainees' expectations is hoped to improve the future training experiences.

I would like to thank all those who were my backbone throughout this work. The Co-author Gill AITKEN and the research interviewees as well my supportive family; Mother, husband, daughters and sons. Thank you dear all for your love and support.

Charmaz K (2011): Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. Sage Publications, Los Angeles-London-New Delhi-Singapore-Washington DC.

Collins JP and Gough IR (2010): An academy of surgical educators: sustaining education – enhancing innovation and scholarship. ANZ J Surg 80: 13–17.

Debas H. T., Bass B. L., Brennan M.F., Flynn T. C., Folse J. R., Freischlag J. A., Friedmann P., Greenfield L. J., Jones R. S., Lewis F. R. Jr., Malangoni M. A., Pellegrini C. A., Rose E. A., Sachdeva A. K., Sheldon G. F., Turner P. L., Warshaw A. L., Welling R. E., and Zinner M. J. (2005): American Surgical Association Blue Ribbon Committee Report on Surgical Education: 2004. Annals of Surgery. 241(1): 1-8.

Hamdorf JM, Hall JC. (2000): Acquiring surgical skills. Br J Surg.; 87(1):28–37.

Lingard L, and Kennedy T.J. (2010): Qualitative research methods in medical education. In Understanding Medical Education: Evidence, Theory and Practice. Edited by Swanwick T. ASME, Ch. 22, 323-335.

Patton M.Q. (2002): Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Sage Publications. Thousand Oaks. London. New Delhi

Reid M., Ker J.S., Dunkley M.P., Williams B. and Steele R.J.C. (2000): Training specialist registrars in general surgery: a qualitative study in Tayside. J.R. Coll. Surg. Edinb.; 45: 304-310.

Weiss R.S. (1995): Learning From Strangers: The Art and Method of Qualitative Interview Study. The Free Press - A division of Simon & Schuster, New York-USA. Ebook downloaded on Samsung Galaxy Tablet from:

http://ifile.it/hfioy0/ebooksclub.org__Learning_from_strangers__the_art_and_method_of_qualitative_interview_studies.epub retrieved on 30/10/2011

Send Email

Send Email