| Theme: 7II Simulation and Simulated Patients | |||

|

||||||

| Simulated medical consultations with an extended debriefing: students perception of learning outcomes |

|

|||||

|

||||||

In Brazil, medical students begin to perform supervised consultations since the 4th-year of their 6-year undergraduate course. As teachers, we often observe their difficulties with the affective dimension of the consultation, even when they are comfortable with technical issues related to diagnosis and treatment. It seems that students sometimes do not feel legitimate in the role of doctors. This contrast between what they know and what they can actually deliver reduces the success of the physician-patient relationship and the beneficial outcomes of the consultation, including students’ own satisfaction.

One possible explanation for this is what happens in the development of their professional identity throughout the medical course. Most medical students in Brazil are young, never worked, and come from small families. In this context, they had few personal experiences associated with illness, loss and failure, and thus fewer opportunities to reflect on these issues. With this background, they come in contact with the suffering related to patients' illnesses and the social inequality of our country. The lack of formal activities directed to reflective practice, the subspecialized and disease-centered medicine, and the contact with negative role models contribute to the affective detachment between the medical student and the patients.

The authors conducted a simulated medical consultations activity using standardized patients, with an in-depth debriefing based on the feelings of the patient and the student. The clinical cases were developed with a mixture of technical and human challenges related to the doctor-patient relationship, and a particular concern in defining the emotional atmosphere of the consultations. Feedback was conducted in the form of an extended in-depth debriefing, lasting at least 2 hours, with the participation of students, teachers and actors. The structure of the debriefing, especially the availability of time, allowed us to address the students’ and patients’ feelings coming from the simulated consultations, as well as the consequences of this emotional interaction.

Fourth- and sixth-year medical students (n=344) participated and completed an anonymous questionnaire about the activity and the learning outcomes. The purpose of this study was to record the opinions of students about this new kind of training, especially regarding the way they handled a feedback that deals with their feelings and encourages a great deal of personal exposure.

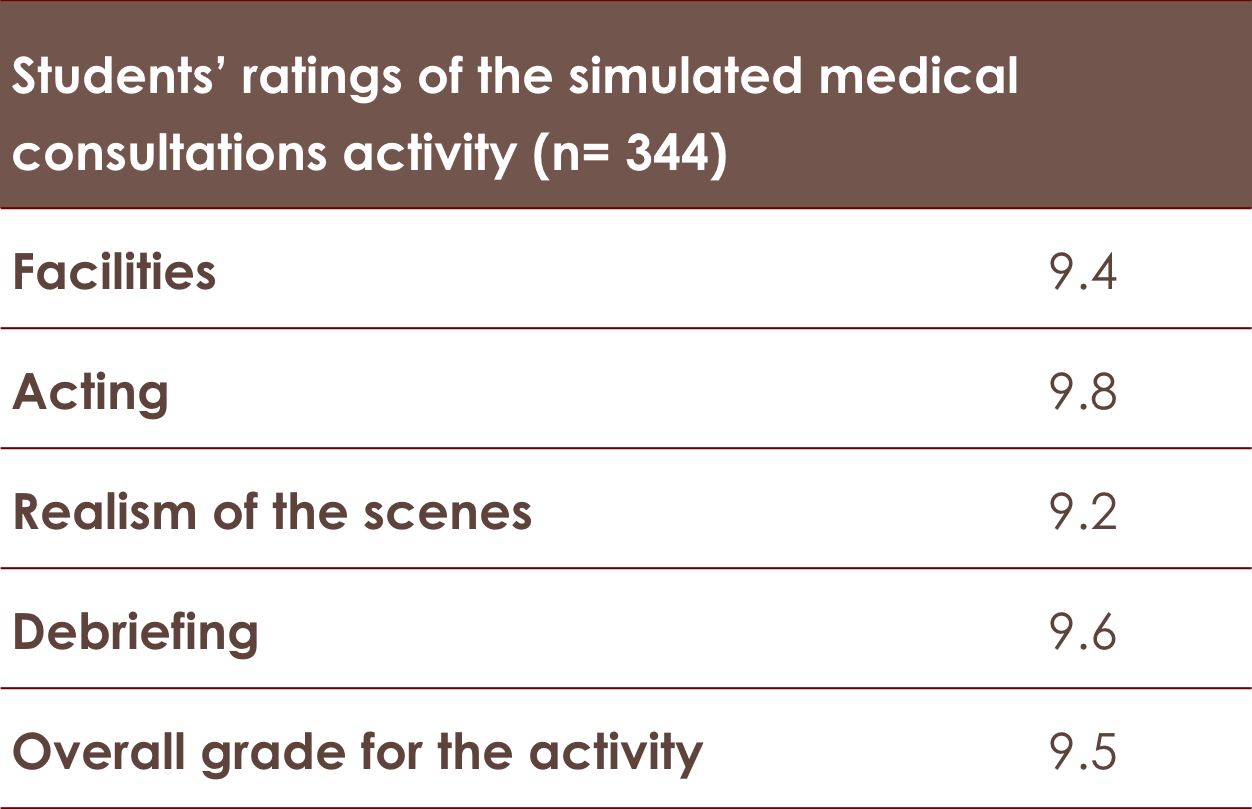

The 344 fourth- and sixth-year medical students rated particular elements of the activity, as shown in the table below:

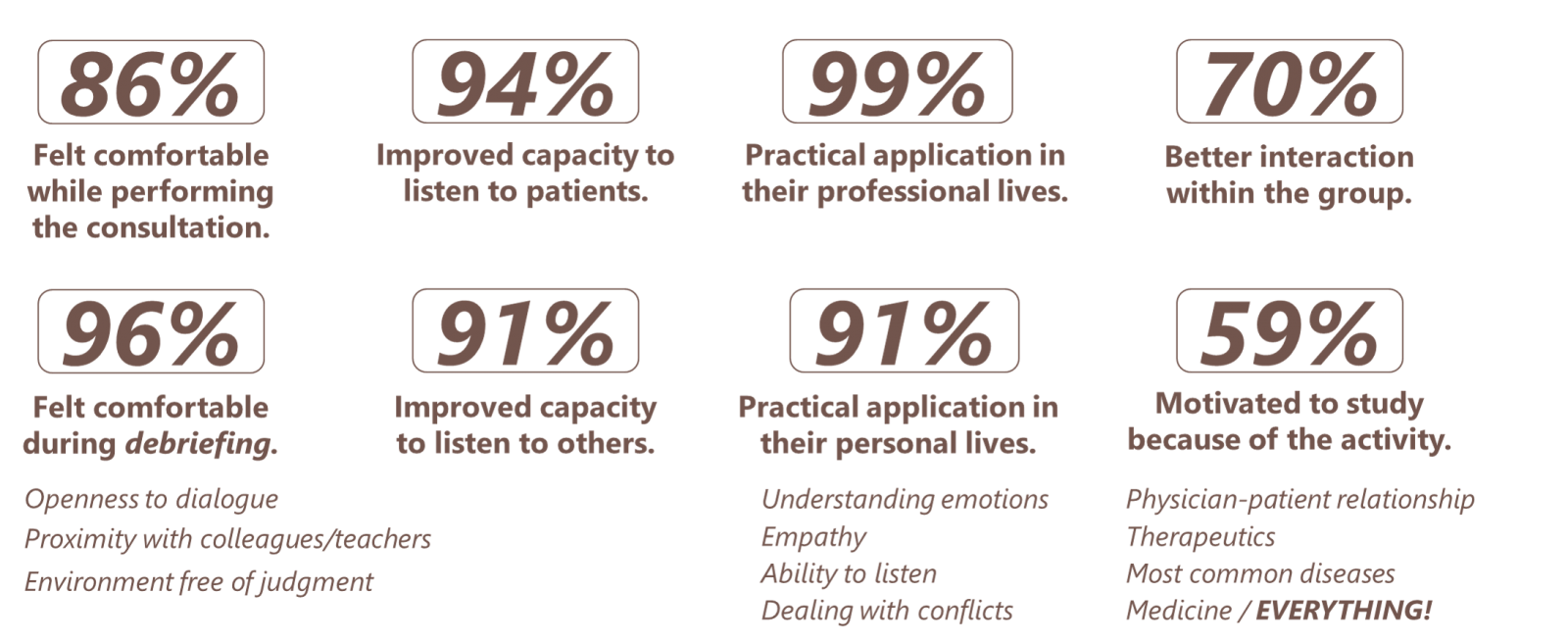

Students reported their perceptions regarding aspects of the activity and its impact on their academic and professional daily lives:

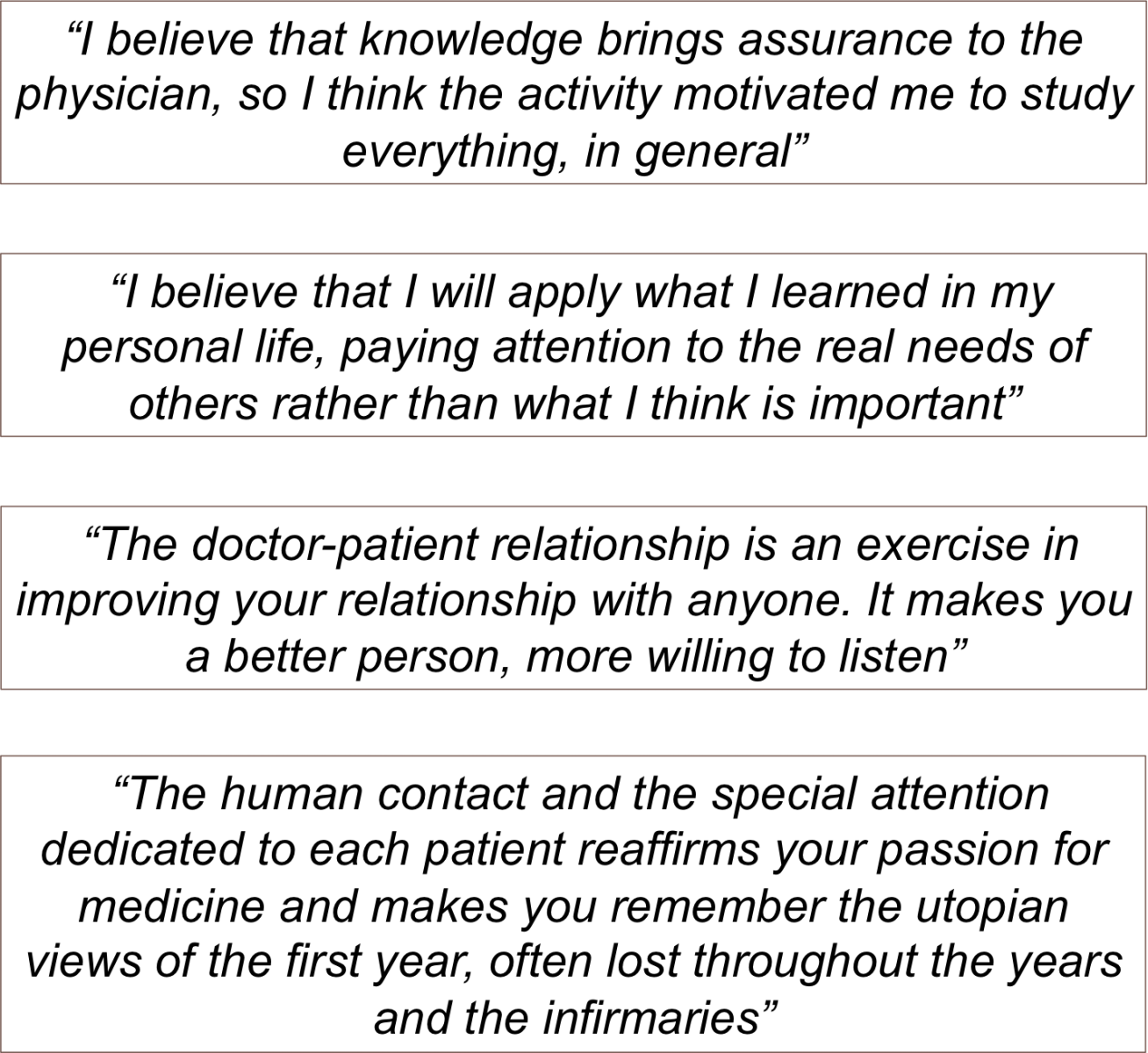

Some sentences written by students seemed most representative of their opinions:

A safe learning environment, free of judgment and with purely formative goals, allows medical students to start the reflective process that will ultimately place them as protagonists of their professional future. That kind of environment should also prevail between doctor and patient during a consultation, so that the patient feels comfortable sharing their experiences and thoughts, and the doctor has the legitimacy and intimacy required to comment, suggest and make proposals. The teacher, as well as the physician, must be prepared to deal with intense emotional reactions, being available to assist and support.

When medical students are encouraged to share what they feel about the doctor-patient relationship in an academic activity, they may feel more comfortable to encourage their patients to share their feelings about the disease and its consequences. Moreover, if we deal with the students’ emotions in a positive way, guiding them and giving legitimacy to what they feel, they will probably do the same with their patients in a consultation.

Send Email

Send Email