Theme

4JJ Interprofessional education 1

INSTITUTION

University of British Columbia - General Surgery

University of Ottawa - Paediatrics

University of British Columbia - Medicine

Interdisciplinary healthcare education is the new direction of medical programs. It is slowly being introduced into medical school as well as medical practice.1,2

The College of Physician and Surgeons of Canada has created a CanMEDS Framework, which defines key competencies required for medical education, practice and improved patient outcomes. In order to appropriately fulfill the 7 CanMEDS competencies students and physicians must, amongst other things, recognize the limits of their knowledge, seek consultation from other health professionals when appropriate and participate effectively in interprofessional healthcare teams.3 Effective communication and conflict resolution are of paramount importance in such a framework. This paradigm shift will help current and future physicians to better understand the roles of other allied healthcare professionals so that they can maximize the effectiveness of the team and thus the benefit to society.

Although medical schools are currently in the process of implementing this paradigm shift, the benefits of interdisciplinary education and collaboration have not yet been widely disseminated throughout the health care system. This was evident in a recent study by Williamson et al. that analyzed 2000 incident reports and found that 80% of the medical errors reported were due to poor inter-professional communication.4

As second year residents with previous healthcare backgrounds in nursing and pharmacy we have experienced the challenges and successes associated with interdisciplinary teamwork and communication. As such, when given the opportunity to do a research project for our Doctor, Patient and Society (DPAS) course, we eagerly elected to explore the dynamics of interdisciplinary collaboration in an attempt to identify current gaps in knowledge and practice as well as possible solutions. We hope that our findings, when shared with various healthcare disciplines, might improve interdisciplinary education, teamwork, and ultimately patient care and outcomes.

We designed and electronically distributed a 27-question Googledoc survey to registered healthcare professionals via the Faculties of Pharmacy, Nursing and Medicine as well as an advertisement in the BC Medical Journal. Participants were asked to begin by rating their self-perceived current knowledge of their own scope of practice as well as those of the other professions. The following survey questions were used to assess the respondents’ knowledge of the various scopes of practice (medicine, pharmacy, nursing). The questions were taken from each professions scope of practice document published by their respective governing body, and a wide variety of questions were chosen to represent the broad scope of each profession. Participants were asked to complete every question for all three disciplines.

Answers to the survey were sent to all invited participants following closure of the survey period. We collected the data and presented our findings in a lunchtime lecture for pharmacy, medical and nursing students and faculty.

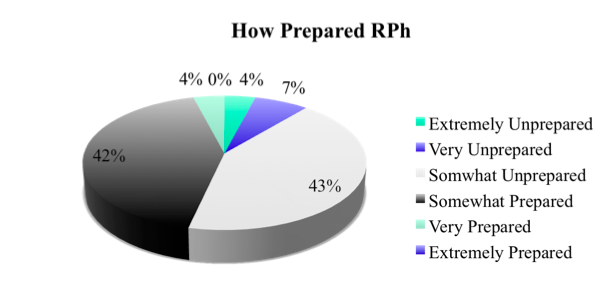

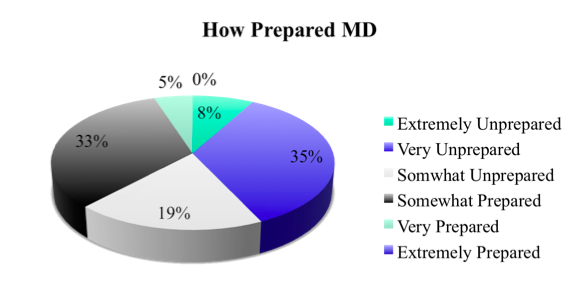

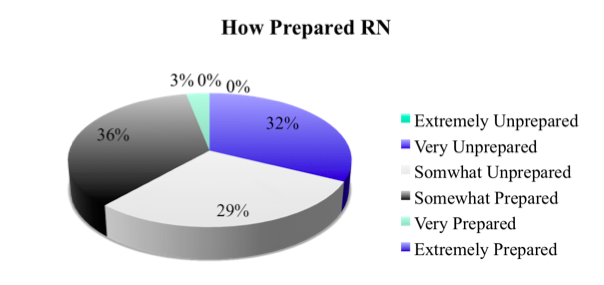

Ninety-seven physicians, registered nurses and pharmacists responded to the survey collectively. The results for the survey demonstrated 3 important points for consideration: firstly, over half of the participants believed inter-professional education was ‘very important’ (50% RPh, 62% MD, 55% RN); secondly, participants believed they were either ‘somewhat unprepared’ (43% RPh, 19% MD, 29% RN) or ‘somewhat prepared’ (42% RPh, 33%MD, 36% RN) for effective inter-professional practice through their healthcare training program; lastly, every profession performed worse on questions regarding their own scope of practice than they predicted.

Approximately half of participants (RPh, MD, RN) believed that they were ‘extremely knowledgeable’ about their own scope of practice while their actual scores on profession-specific questions ranged from 50.5-72.3%. The majority of participants (RPh, MD, RN) claimed that they were ‘somewhat knowledgeable’ about other scopes of practice while their actual scores on questions regarding other scopes of practice averaged 60.5%.

Our study has inspired intrigue in students and faculty members alike in all three disciplines. We have shared our findings with faculty members interested in improving interdisciplinary education at the University if British Columbia in the hope that it will help to create change. We have also been working with students who are interested in elaborating on this project, possibly through collaboration with other faculties.

Although the quest for seamless inter-professional collaboration may at times seem to be a daunting and insurmountable task, we are certain that it is achievable. We hope that our study will inspire enthusiasm that will help lead to changes in education and practice. It is our privilege to be part of this transition towards interdisciplinary education, teamwork and ultimately improved patient care and outcomes.

Interdisciplinary healthcare is here and medical education needs to incorporate more interdisciplinary points into the curriculum to better prepare future physicians for the new work place. Currently practicing MDs, pharmacists and nurses do not feel like they were prepared for interprofessional healthcare teams when they were students.

Thank you to Dr. Catherine Anderson at UBC, the UBC College of Health Disciplines, UBC Faculty of Medicine, Pharmacy and Nursing.

1. Chan AK, Wood V. Preparing Tomorrow’s Healthcare Providers for Interprofessional Collaborative Patient-Centred Practice Today. UBCMJ 2010;1(2):22-24.

2. World Health Organization (WHO. Learning outcomes for interprofessional education (IPE): literature review and synthesis. 2008: Unpublished document. Available at: URL: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2010/WHO_HRH_HPN_10.3_eng.pdf.

3. College of Physician and Surgeons of Canada. CanMEDS 2005 Framework. Accessed June 14, 2011 from: URL: http://rcpsc.medical.org/canmeds/bestpractices/framework_e.pdf

4. Williamson, J., Webb, R., Sellen, A., Runciman, W.B., & Van derWalt, J.H. Human failure: Analysis of 2000 incident reports. Anesthesia Intensive Care 1993;21(5):678-83.

Send Email

Send Email